Can US visa issuance get back on track?

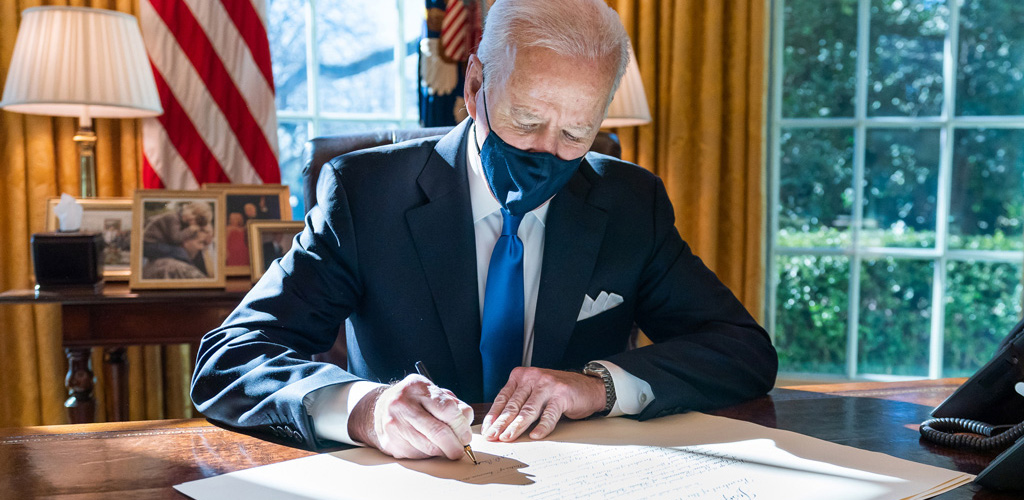

The election of Joe Biden as US president signalled a change in direction in both domestic and international US policy. But how will the result affect US international education – can it expect a ‘Biden bounce’, or will it be more of a ‘not Trump bump’? Viggo Stacey reports.

The message from the top echelons of government is going to be important for international education and international student recruitment, isn’t it? For the vast majority of US international educators, four years of the Trump administration brought with it an array of headache-inducing policies that made life, and their jobs, difficult to say the least.

Take for example policies such as the so-called ‘Muslim Ban’ or warnings from the then acting Homeland Security secretary, Chad Wolf, that his department had “concerns” with the temporary employment opportunity, Optional Practical Training.

The Financial Times even reported White House aides encouraged president Trump to stop processing student visas to Chinese nationals in 2018. That cohort of students represents more than 30 per cent of all international students in the US.

While visa issuance did not stop exactly, it seems that it got pretty close. According to State Department data, from February 2020 to January 2021, only 48 F-1 student visas were issued, comparing 103,086 F-1 issued in the previous 12-month period.

Lobbying and publicity about a hiatus in visa processing at many US consulates around the world means stakeholders are hopeful that the National Interest Exception for students arriving in the US from China, Brazil, Europe and South Africa from August 2021 is a sign of intent to admit on a much larger scale from China.

When Joe Biden was elected to the White House in late 2020, it was unsurprising that US international education experts reacted, on the whole, with glee. But while statistics indicate that fewer international students have been choosing the US, its institutions remain the gold standard. If rankings are your thing, of the world’s top 100 institutions according to THE’s World University Ranking, 37 are in the US, while QS ranks 27 US schools in its top 100.

In fact, the drop of the international student population in the US under Trump was not relatively an historic drop. Although in 2019/20, 1.8 per cent fewer international students were studying in the US, it was not as dramatic as the 2.4 per cent decline experienced following 9/11 in 2003/04.

It remains unclear how the global health pandemic will impact figures – and the visa freeze which impossible access to US consulates might have forced. Nonetheless, Biden’s agenda could prove instrumental in improving the country’s standing globally as a study destination, stakeholders suggest.

It seems unlikely prospective international students will choose the US because there is a new 78-year-old white man residing in the White House. It’s difficult to imagine a student in India look to Biden and think, ‘now that is what I call a pull factor’. Or is it?

One survey of 800 current and prospective students, carried out by Net Natives, found that six in 10 indicated they would be more likely to study in the under a Biden presidency, with North American and African students having the most increased likelihood of studying in the US.

Generally, international students as a whole are over twice as likely to feel safe and welcome in the US under the Biden administration, it found. Likewise, an IDP Connect survey found that 76 per cent said that Biden’s election had led to an improved perception of the US.

“When it comes to a `Biden boost’, we are hearing that international students are encouraged by the election results, but more will need to be done in terms of policy to get them back,” explains Robin Helms, American Council on Education’s assistant vice president for Learning and Engagement.

According to ACE, the Trump administration “spent the entirety of its tenure chipping away at immigration and policies that have for years supported international students and scholars”. NAFSk.„ ACE and the President’s Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration all pointed to the Biden-Harris administration’s welcoming stance towards international students following the election.

The long list of policy priorities the bodies have advocated for include reversing the proposed rule to eliminate duration of status, a proposal that would mean it would be unclear whether international students can maintain their legal status in the country through the completion of their studies.

Other items on the list include overturning “harmful” visa and immigration policies, such as the travel bans; extending current dual intent policy to international students in F-status to allow them the chance to remain in the US after completing their studies (dual intent is already permitted in some non-immigrant visas, such as H-1Bs); and preserving post-study learning opportunities, such as OPT.

Writing in The PIE in November 2020, director of International Student and Scholar Services at American University, Senem Serpil Bakar, featured in her wishlist an increase in the Fulbright program’s scope, and a high-level acknowledgement of international student contributions. Bakar also called for “meaningful immigration laws”.

Other items on the list include extending current dual intent policy to international students in F-status

ACE, NAFSA and the President’s Alliance have also highlighted creating a direct path to lawful permanent residence via green cards to in-ternational graduates of US institutions. ACE “especially” supports proposals that would allow STEM degree students to remain in the US. NAF-SA has also made the call to create a national international education strategy.

“While the Biden administration is still in transition mode, we’ve seen some shifts in the political climate indicating that the US is poised to re-en-gage with global diplomacy and immigration-friendly policy,” Emily Hassenstab, interim director of International Programs at University of Ne-braska at Omaha adds. “These shifts and new grant opportunities focusing on international programming and engagement is a great signal that the US will continue to welcome international students.”

Open Doors figures indicate that students are looking for opportunities to remain in the country and work, possibly leading to immigration possibilities. In the previous decade, students on the OPT program increased from 67,804 in 2009/10 to 223,539 in 2019/20. Under the Trump administration, this opportunity was often under attack from the White House. The Biden administration has already allowed a Trump-era suspension on H-1B visa holders to expire in April.

Institutions in countries such as Canada and Australia have seen international student enrolments rise thanks in part to government laws allowing pathways to immigration and work following graduation from institutions in the countries. Now that the UK will introduce its graduate work route in summer 2021, there are calls for the US to give international students a similar nod for work opportunities.

“We need a flexible modern immigration system that matches this aspiration [to recruit and retain the best talent the world],” notes Rosemary Max, executive director, Global Engagement at Oakland University’s Office of Global Engagement.

“Between the changes in administration and the Covid-19 pandemic, there are some barriers to international education that still need to be resolved: Delayed immigration policy reform, a backlog of visa applications, varying travel restrictions, and underinvestment in immigration processing,” agrees Hassenstab. “International education will definitely get its mojo back but we know we have work to do to get there.”

Senior counsellor at the llE, Peggy Blumenthal, highlighted in April that uncertainty about whether US-China relations improving under Biden would “not likely to influence students’ enrolment decisions for fall 2021, since students and their families begin planning for study abroad years in advance”.

A welcoming tone and efforts to address the backlog of visa applications are al-ready being noticed

Despite documented problems with visa issuance out of China, a welcoming tone and efforts to address the backlog of visa applications and OPT approvals from the Biden administration, are “already being noticed with relief among host campuses and potential applicants”, she adds.

Opening consulates and restarting visa processing is oft remarked as a priority. “In the short term, we hope that the US State Department will not only open its consulates around the world (and in China, in particular), but also that they are prepared to streamline application processes around the globe to clear the significant backlogs that currently exist in time for students to return to the US this fall,” explains Sherif Barsoum, associate vice president for Global Services at New York University.

“Recent steps taken by the White House have clearly resulted in positive changes for our international student population, including, importantly, USCIS’s increased flexibility in response to challenges that have arisen due to Covid-19,” he says.

However, a 2020 pre-election New Oriental Education survey of 6,673 responses in 34 provinces in China found that Chinese students were turning towards the UK rather than the US as a study destination, with 42 per cent choosing the UK as the top choice country to study abroad in, compared with 37 per cent of students choosing the US.

At home in the US, Pew Research in March found that the majority of people (55 per cent) now support limiting Chinese students studying in the US. Reports of anti-Asian xenophobia has also been a worrying trend across the US, as in many other countries. Demographic data publisher and

Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders policy research non-profit AAPI Data has warned that the “fundamental reality is that there’s an in-crease in the number of Asian Americans who feel unsafe”. Welcoming messaging from across the sector is vital here, stakeholders suggest.

“International education in the US is varied and there are so many schools. Having a welcoming environment for international students will help all institutions as well as our local and state economies,” says Rosemary Max at Oakland University.

Northeastern University has seen its international applicant pool increase by six per cent in 2021, a “modest upward trend” which is put down to likely the result of the past months’ restrictions on travel and the difficulty in obtaining visas to study in the US.

Hassenstab at University of Nebraska at Omaha says UNO’s support of students during the pandemic led to “historic highs in Fall 2020 includ-ing the largest student body in nearly 30 years and the highest year-over-year retention rate in university history”, including increases among first-time freshman minority students, undergraduate minority students, and graduate minority students; as well as retention of more than 80 per cent of all female, Hispanic, and Asian students from Fall 2019’s freshman class.

Interestingly, NYU’s New York, Abu Dhabi, and Shanghai campuses saw an increase of some 15,000 applications in 2021, totalling more than 100,000 applications — with 19% of admittees being international students. Other traditionally popular institutions have seen similar interest increases, but other options are gaining traction.

Anecdotal evidence from senior education adviser at the US Embassy Abuja, Nigeria, Folashade Adebayo has suggested students and parents are increasingly looking to historically Black college or university for affordability or scholarship opportunities. As a graduate of Howard University, vice president Kamala Harris has helped to put HBCUs in the limelight. “Latinx students and immigrant students see Black schools as a safe space with the rise of Fascism and xenophobia,” Patricia Williams Lessane, associate vice president for academic affairs at Morgan State University, said in 2020.

Other advocates, such as Jing Luan, provost of International Affairs of San Mateo County Community College District and president of American International Recruitment Council, praise the affordability and access that community colleges offer.

While it “is too early to know if there will be a Biden bounce for international students”, the sector is hoping for one, Max explains. “We especially hope students from China will be able to return to the United States in time for Fall 2021. They are still unable to come to the United States.”

And optimism is evident. “The election results combined with vaccines are bringing about a sense of optimism, and excitement for what’s to come,” notes Helms at the ACE. “Even though we recognise there are still plenty of challenges, the last few years have proven just how strong we are as a field.”

“I am hopeful that colleges and universities across the board will see growth as the global Covid recovery continues,” Barsoum says, “and it becomes clear to prospective students — and their families — that the US is waiting to welcome them with open arms — or perhaps better still, an elbow bump!”

Original article: https://thepiereview.mydigitalpublication.com/display_article.php?id=3998969&view=703063